Claim free conveyancing is an LPLC Practice Risk Guide produced to help practitioners identify and avoid the most common mistakes resulting in claims in conveyancing transactions. The guide aims to raise awareness of how and why mistakes occur, and put practitioners in a better position to stay claim free.

What's on this page?

- Introduction

- Cyber risks

- The causes of claims

- Glossary

- The most common mistakes

- LPLC Vendor’s Practitioner Checklist

- LPLC's Purchaser’s Practitioner Checklist

- APPENDIX ONE: Suggested form of letter to client if requested to prepare a section 32 statement in a hurry

- APPENDIX TWO: Owner builder obligations

- APPENDIX THREE: Rescission Notice

- APPENDIX FOUR: Owners corporation certificate items and issues to be aware of

Introduction

Claims against practitioners arising from conveyancing transactions are regularly between 25 and 30 percent of claims by cost and number each year. The factors that contribute to these statistics include that conveyancing is a very technical area of the law often with high volumes and low margins which can result in simple but costly errors if precautions aren’t taken. This publication is produced to help practitioners avoid the most common conveyancing mistakes which have resulted in claims.

The move to electronic settlements has helped avoid some historical claims such as delay in lodging transfers but increased other risks such as paying money to the wrong account. Many of the mistakes causing claims occur outside of the electronic property settlement platform and relate to a lack of legal knowledge, a failure to use effective systems, precedents and processes, as well as poor communication.

This guide is not a comprehensive text on how to run a conveyance but it provides examples and information about the most common mistakes practitioners make in conveyancing transactions and recommendations for how to avoid these mistakes. There are consolidated checklists for vendor and purchaser’s practitioners to help avoid the biggest risks.

Cyber risks

Conveyancing transactions are a target for cyber criminals because of the large sums of money being transferred. Most commonly the email account of the lawyer, client or real estate agent in the conveyance is infiltrated by cyber criminals. The criminals intercept an email with bank account details in it or send a fake email purporting to be from a client or lawyer with fake bank account details in it instructing money be paid to a cyber criminal’s bank account. If the fraud is not detected quickly the money is paid and cannot be recovered.

| CLAIM EXAMPLE A firm acted for a vendor who sold a country property in July 2017 for $295,000 with final settlement due in October. Shortly before settlement, the firm emailed the vendor client confirming payout details and requesting the client’s bank account details. The client received the email and responded but the firm did not receive that response. Instead they received an email, purportedly from the client but actually from a cyber criminal, setting out details of the account into which the net settlement proceeds should be paid. The net proceeds from the sale was paid to the cyber criminal’s bank account. A few days after settlement when the client did not receive the settlement funds they phoned the firm to ask when they would receive the proceeds. On realising the earlier ‘email instructions’ were fraudulent, the principal’s secretary swiftly contacted the firm’s paying bank as well as the receiving bank into which the funds had been deposited. Fortunately, most of the money was still in the fraudsters account and was able to be frozen by the bank and recovered. However, a claim was made against the firm for the small shortfall on the basis of a breach of trust in paying settlement money to an account the client had not authorised. | ||

| Our recommendations LPLC has initiated and continues to roll out a multi-faceted risk management campaign addressing these cyber fraud risks within the profession. Our cyber security resources can be found on a dedicated section of our website and includes a cyber security guide for lawyers. Firms should read the guide and implement recommendations in each of the five sections of the guide to protect against cyber-attack. |

The causes of claims

The three major underlying causes of claims in order of highest to lowest are:

1. Failure to manage the legal issues

Claims continue to arise where the practitioner does not know the law, overlooked an issue or more common, did not collect enough facts to apply the right law. Owner builder requirements are a good example where not enough information is obtained and advice on the legal issue is not given.

2. Poor communication

These claims often involve the failure to give the client enough information to make an informed decision.

In addition, many clients have never retained a lawyer before and do not know how to work effectively with them. This lack of understanding also contributes to claims that could have been avoided or minimised if there had been better communication between the firm and the client about working together.

To help practitioners manage their clients’ expectations as well as explain both the client’s and lawyer’s roles and obligations in the relationship LPLC has developed a sample information brochure Working together – roles and obligations to illustrate what could be done.

3. Poor systems, precedents and processes

This is about how firms actually do the work. Mistake occur because the practitioner doesn’t use workflows or checklists to make sure things are not overlooked, or they don’t use precedent letters with all the relevant advice in them or regularly review and update their precedents.

Being vigilant about keeping up with the changes to law in conveyancing, and diligently considering the legal issues and managing the client and the matter can go a long way to minimising exposure to conveyancing claims.

Glossary

In this guide:

- SLA refers to the Sale of Land Act 1962 (Vic)

- section 32 statement refers to the statement required pursuant to section 32 of the SLA.

The most common mistakes

Below we provide descriptions and examples of those common mistakes and LPLC's recommendations for how to avoid them.

Mistakes involving duty, Capital Gains Tax and land tax are a continual source of conveyancing claims. In many instances practitioners fail to appreciate that a proposed transaction will result in an increase in tax being paid. Practitioners need to have sufficient knowledge of tax and duty consequences to appreciate the issues and either advise clients about the tax consequences or refer them to a tax expert.

Duty

Duty mistakes typically happen when practitioners don’t understand the legislation dealing with:

• Nomination of new purchaser

• Sale of a family farm

• Transfers to specific beneficiary of a trust.

NOMINATIONS

Section 32J of the Duties Act 2000 (Vic) sets out the basis on which duty will be payable on transfers.

Double duty will be payable when a vendor agrees to transfer land to an original purchaser and then to a subsequent purchaser, often through nomination, in two circumstances:

• The original purchaser ‘undertook or participated in land development’ before the new purchaser was nominated

• The subsequent purchaser paid or is liable to pay more consideration than the original purchaser.

’Land development’ is defined broadly and includes:

• Preparing a plan of subdivision or taking steps to have it registered

• Applying for or obtaining a planning permit

• Applying for or obtaining a building permit or approval

• Doing anything on the land for which a building permit or approval would be required

• Requesting an amendment to a planning scheme that would affect the land

• Developing or changing the land in any way which would increase its value.

See LPLC’s article Double duty and nominations for more information and suggested wording about nomination risks.

FAMILY FARM

Claims have arisen where practitioners acting in the transfer of family farms have not understood the conditions required to qualify for the exemption for duty in Section 56 of the Duties Act. In particular, if the transferor or transferee is a trust, all of the beneficiaries of the trust must be family members to qualify for an exemption from duty.

See LPLC’s article Trusts and family farm transfers for more information.

Duty claims also arise where a practitioner provides advice without first checking whether the relevant legislation has been amended.

TRANSFER TO SPECIFIC BENEFICIARY OF A TRUST

Under section 36A of the Duties Act the transfer of a property from a trust to a beneficiary of the trust will be exempt from stamp duty if the Commissioner is satisfied that the transfer is not part of a sale or other arrangement under which there exists any consideration for the transfer. In many instances the transfer is accompanied by forgiveness of a loan which the Commissioner considers is consideration. The practitioner is then accused of not properly advising of the consequences of forgiving the loan in close proximity to transferring the property.

While there are often arguments to say that the long-term benefits of transferring the asset to the beneficiary outweighs the duty payable, the client should be given an opportunity to make an informed choice.

FOREIGN RESIDENT ADDITIONAL DUTY

Practitioners incur claims for failing to advise clients that there is additional duty payable for foreign natural persons, foreign corporations and trustees of a foreign trust. The clients allege that if they had been advised they would have structured their arrangements differently. Foreign entities are defined on the SRO website.

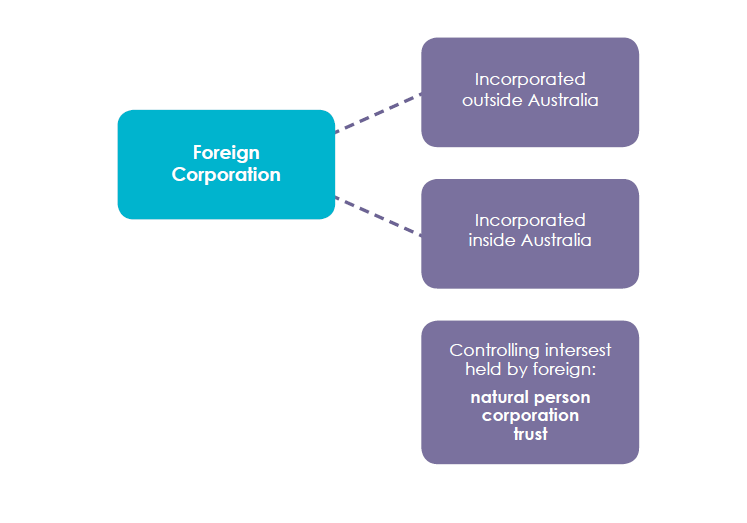

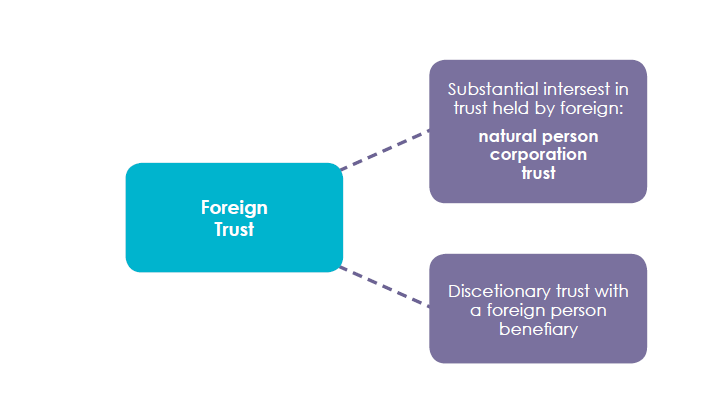

The definitions practitioners sometimes don’t know are: a foreign corporation is any corporation incorporated outside Australia or if incorporated in Australia the controlling interest is held by a foreign

natural person, foreign corporation or foreign trust. A foreign trust is a trust where a substantial interest is held by foreign natural person, foreign corporation or another foreign trust. From March 2020 the SRO treat a discretionary trust that has a foreign person as a beneficiary as a foreign trust.

There are various exemptions that may apply but in general the extra duty payable by a foreign purchaser of residential property is eight percent. Gifting residential property to a foreign party also incurs the extra duty.

Capital gains tax

Capital Gains Tax (CGT) claims have arisen where there is a related party transfer such as a transfer of land from a trustee to a beneficiary, between spouses and/or between related corporate entities. While in many of these situations there is no duty payable practitioners forget to consider capital gains tax. Some clients may think such transfers are simply but these sorts of transfers are anything but simple and should be treated no differently to an arm’s length conveyance.

| CLAIM EXAMPLE No advice about CGT In the decision of Snopkowski v Jones (Legal Practice) [2008] VCAT 1943, the tribunal found the practitioner had been asked by the client in general terms if any liability would flow from him transferring his property to his wife’s name. The practitioner advised the couple that the procedure to transfer the property would be relatively simple and the only cost would be the practitioner’s fees and a Titles Office fee. The practitioner said the issue of CGT did not even occur to her. The tribunal held that when a practitioner is asked whether there would be any financial implications upon transfer of the property, it is reasonable to expect the practitioner would at least advise the clients to seek advice from their accountant or a tax lawyer relating to the issue of CGT. By failing to alert the clients to the possibility of CGT liability, the practitioner had breached the standard of care required of a practitioner in such a situation. | ||

CGT can also inadvertently be incurred by creating a life interest or granting licences over assets. To read further about these CGT consequences see our article Beware of tax issues when advising your client and the following ATO tax rulings:

• TD 2018/15 concerning the CGT consequences of granting a licence, easement or profit à prendre over an asset

• TR2006/14 which deals with the CGT consequences of creating life and remainder interests in property.

Land Tax

BUYING ON BEHALF OF A TRUST

Part 3 of Schedule 1 of the Land Tax Act 2005 (Vic) sets out the land tax rates for land owned by trusts. These rates are higher than for land owned outside of a trust.

Most land tax claims arise when the practitioner fails to provide the SRO form 8 notice of acquisition by a trust to the SRO and as a result the owner pays land tax for a period of time at the lower rate. When it is discovered penalties and interest are imposed.

In some cases the wrong form was provided, either because the practitioner did not know the client was buying the land on behalf of a trust or did not stop to think about which form should be used. In some instances the form is not given to the SRO at all because it was not made clear who was responsible for completing it.

The key to avoiding these claims is to ask the client whether they are purchasing in a trustee capacity and check all conveyancing documents for any reference to a ‘trust’, especially the contract of sale and any nomination form. If the client is buying on behalf of a trust advise them that higher land tax will be incurred unless an exclusion applies (See section 46A of the Land Tax Act 2005 (Vic)). Confirm the client’s instructions in writing.

You should also advise the client of the need to give notice and agree who is responsible for giving notice – the client or the practitioner.

LAND TAX CERTIFICATE

When acting for a purchaser, you should always obtain a land tax certificate so the purchaser is protected pursuant to section 96(4) of the Land Tax Act in the event the land tax is altered later. That is, only the amount in the certificate can constitute a charge on the land.

BASIS OF LAND TAX ADJUSTMENT

When advising a purchaser client precontract check the basis on which the land tax is to be adjusted. If it is to adjusted on a proportionate basis advise the client that this may be a much larger amount than on a single holding basis.

For more information about land tax refer to the SRO website and search land tax and trusts as well as following the LPLC publications:

• Beware land tax issues when advising your client

• Land can be taxing

• More land tax woes

CLAIM EXAMPLE

Was the purchaser a trustee?

A practitioner acted for a client purchasing a house marketed as a development site with the potential for a ‘number of premium townhouses STCA’. After signing the contract the individual purchaser nominated a company as substitute purchaser. The matter settled in September 2011.

In early 2016 the SRO determined that the property was subject to the land tax surcharge for trusts and sought additional land tax of approximately $20,000.

The client contacted the practitioner and sought an explanation as to why notice was not given to the SRO of the acquisition by a trust.

In this claim the practitioner did not ask whether the purchaser was a trustee and the client did not volunteer the information. In recognition that both the client and practitioner were to blame for failing to give notice, the claim settled with a small payment to the client.

In a similar claim which resulted in a bigger payment to the client, the practitioner prepared the nomination form which referred to the nominee company in its capacity as trustee of a trust. The practitioner failed to either give notice to the SRO about the trust acquisition or tell the client to do this.

Our recommendations

Review and understand the requirements of section 32J of the Duties Act 2000 (Vic) in relation to nominations and duty

- Speak to your purchaser client at the start of a retainer and ask them what they intend to do with the property so you can discuss the risks of taking development steps before nominating

- Include advice in your initial precedent letter to purchaser clients about the risks of double duty when nominating if any land development, including lodging planning applications, has occurred

- Advise your purchaser client that there is additional duty payable for foreign natural persons, foreign corporations and trustees of a foreign trust

- Understand the definitions of foreign entities as defined on the SRO website, particularly that a discretionary trust with a foreign person beneficiary is considered a foreign trust

- Review and understand the exemptions for duty in section 56 of the Duties Act, in particular, if the transferor or transferee is a trust, all of the beneficiaries of the trust must be family members to qualify for an exemption from duty

- Review and understand the exemptions for duty in section 36A of the Duties Act when a trust transfers duty to a beneficiary and what may be deemed consideration

- Understand when capital gains tax may be triggered and advise your client to seek financial advice if the structure of the transaction could trigger capital gains tax

- Ask the client whether they are purchasing in a trustee capacity and check all conveyancing documents for any reference to a ‘trust’, especially the contract of sale and any nomination form

- If the client is buying on behalf of a trust advise them that:

- higher land tax will be incurred unless an exclusion applies (See section 46A of the Land Tax Act 2005 (Vic))

- notice of the aquisition must be given to the State Revenue Office and agree who is responsible for providing the LTX-Trust-08-form – the client or the practitioner - When acting for a purchaser, always obtain a land tax certificate so the purchaser is protected pursuant to section 96(4) of the Land Tax Act

- When advising a purchaser client precontract check the basis on which the land tax is to be adjusted. If it is to be adjusted on a proportionate basis advise the client that this may be a much larger amount than on a single holding basis.

Claims involving GST mistakes continue to arise although the mistakes made do not vary greatly from year to year.

Vendors’ practitioners are sued for:

• Failing to include a GST clause in the contract or fill in the GST box in the particulars

• Including the wrong GST clause in the contract (a GST-inclusive clause instead of a GST-exclusive clause) or contradictory clauses in different parts of the contract

• Purporting to apply the margin scheme in circumstances where it was not available, usually because full GS T was paid on the acquisition of the property, or no agreement was reached to apply the margin scheme

• Failing to obtain the professional valuation for margin scheme purposes by the end of the tax period in which settlement fell

• Using the supply of a going concern exemption in circumstances where the strict requirements of section 38-325 of A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 were not met or

• Failing to collect GST at settlement, often because it was wrongly assumed it is not payable such as where the property sold is vacant residential land. Vacant land is not considered to be residential premises and will attract GST.

Purchasers’ practitioners are sued for failing to:

• Provide pre-contractual advice on the existence and consequences of a GST-exclusive clause in the contract

• Protect a commercial purchaser’s entitlement to an input tax credit when purchasing on a GST inclusive basis by failing to exclude the application of the margin scheme

• Advise the purchaser of the effect of a margin scheme provision or a mixed supply on the availability of an input tax credit or

• Ensure the tax invoice provided at settlement was correct.

CLAIMS EXAMPLES

No pre-contract advice on GST

A purchaser of commercial offices informed their practitioner that they wished to purchase the property inclusive of GST and subject to obtaining a change of permitted use to residential. They intended to live there and the office building had originally been a dwelling. The practitioner drafted a special condition dealing with this issue. The parties ultimately agreed that the purchase price be exclusive of GST and the sale be a going concern because it was currently leased. The client intended to terminate the commercial lease several months after settlement and use it as a residence.

The problem with this structure was pointed out to the client by his accountant after the contract was signed. By changing the creditable purpose use from going concern to private use within two and half years after the purchase, GST would become payable.

The client claimed that the practitioner should have provided GST advice prior to the exchange of contracts as to the different GST consequences of treating the property as a dwelling and input taxed compared to an office and sold as a going concern.

The purchaser’s practitioner failed to appreciate the GST consequences where a change of creditable use occurred so soon after the sale.

Margin scheme not available

A practitioner acting for a developer client selling an expensive parcel of land prepared a contract on a GST-exclusive basis with an ‘option’ for the purchaser to request the application of the margin scheme up to one month before settlement. The contract was entered into before the amendments to section 75 of A New Tax System (Goods and Services Tax) Act 1999 (Cwlth) which requires the vendor and the purchaser to agree in writing that the margin scheme is to apply.

The day before settlement the purchaser asked for the margin scheme to be applied and provided a valuation equalling the purchase price resulting in no margin, so no GST payable. The transaction settled on that basis.

After settlement, the vendor’s accountant advised that the margin scheme was not available because full GST had been paid and claimed on the acquisition. The vendor then looked to the purchaser to recover the GST. The purchaser refused and had to be persuaded by expensive litigation to change its position. The vendor’s practitioner was exposed for not having checked the availability of the margin scheme with the client or the accountant when preparing the contract or considering the out of time request for application of the margin scheme by the purchaser.

No pre-contract advice on GST-exclusive clause

A practitioner provided pre-contract advice regarding the client’s proposed purchase of a property on the city fringe which the client wanted to develop into residential apartments. The practitioner provided a comprehensive letter of advice concerning issues with the existing planning permit, contamination, the location of an easement, the timing of proposed demolition works and stamp duty. He otherwise described the contract as ‘standard’. No reference was made to the GST clause which provided the price was GST exclusive and allowed for the application of the margin scheme. The matter proceeded to settlement without any payment of GST.

Shortly after settlement the vendor’s practitioners discovered the oversight and demanded immediate payment. The matter was resolved by payment of margin scheme GST. However, the client maintained he believed the price was GST-inclusive and all calculations on the project had been done on this assumption.

He sued his practitioner for failing to advise on this aspect of the contract. The practitioner had capably advised on the unusual issues in the contract but had overlooked an obvious one.

Our recommendations

When acting for the vendor

- Consider whether the GST threshold criteria are present

- is the vendor registered or required to be registered for GST?

- is the sale in the course or furtherance of an enterprise? - If yes to both questions, consider whether the property being sold will attract GST

-is it vacant land including residential vacant land?

-is it new residential premises including substantially renovated premises?

-is it commercial residential premises?

-is it non-residential premises? - If the property being sold will attract GST, ensure there is a clear GST treatment in the contract. Consult your client about whether the GST clause should be inclusive or exclusive and whether the margin scheme is available and could be applied

- If the margin scheme is to be applied, ensure there is agreement in writing between the parties to this effect. If a professional valuation is required, advise your client in writing of the time frame in which the valuation must be obtained such as by the end of the tax period in which settlement falls

- If the property is farmland, consider whether:

-the farmland exemption (section 38-480) will apply and no GST will be payable on the sale of the freehold, although GST will be payable on livestock, plant and equipment

-the supply of a going concern exemption (section 38-325) will apply and no GST will be payable on the sale of the freehold, livestock, plant and equipment - If the property is tenanted commercial premises, consider whether the going concern technical requirements of section 38-325 and the ATO ruling GSTR 2002/5 are met for no GST to be payable on the sale. In particular:

- the vendor and the purchaser must agree in writing that the supply is of a going concern

- the purchaser is registered or required to be registered for GST

- the sale is not to the tenant

- there is a tenant at the date of supply (usually settlement) and the contract provides for receipt of rents and profits, not vacant possession

- the tenant is in occupation pursuant to a lease or periodic tenancy, not just a tenancy at will

- if there is a temporary vacancy, it will be necessary to show a new tenant is being actively sought or the property is undergoing necessary refurbishment. However, this will not be sufficient if the premises have never been let (see paragraph 151 of ATO ruling GSTR 2002/5)

- the purchaser does not intend to change the creditable use of the property in the near future - Even if you consider the sale will be GST-free under the farmland exemption or as the supply of a going concern, include in the contract a GST-exclusive ‘claw back’ clause, with an expanded definition of GST to include penalties and interest, and a non-merger clause to protect your client. General condition 19 of the standard LIV land contract adequately deals with ‘claw-back’

- If a tax invoice is required, ask your client to provide it. Alternatively, check if your client is GST registered, not just ABN registered, before purporting to prepare a tax invoice on your client’s behalf

- If GST is payable in addition to the purchase price, add it to your checklist to ensure it is collected at settlement.

When acting for the purchaser pre-contract

- Advise on the existence and consequences of any GST-exclusive clause

- If your GST registered commercial purchaser is expecting to claim an input tax credit:

- recommend your client seek advice from their accountant about whether the proposed purchase is a ‘creditable acquisition’ for which an input tax credit can be claimed

- check whether the vendor is GST registered, not just ABN registered, and consider negotiating a special condition that the vendor remain GST registered up to and including the date of supply. Your client will not be entitled to an input tax credit if the vendor is not GST registered at the date of supply - Check whether the margin scheme can be and should be applied. Application of the margin scheme will deprive your client of an input tax credit but would normally be regarded as important if the property is to be redeveloped and sold for residential purposes and has stamp duty implications.

When acting for the purchaser post-contract

- Advise on the existence and consequences of any GST exclusive clause

- If your GST registered commercial purchaser is expecting to claim an input tax credit:

- recommend your client seek advice from their accountant about whether the proposed purchase is a ‘creditable acquisition’ for which an input tax credit can be claimed

- advise the client that they will not be entitled to an input tax credit if the margin scheme is to be applied

- check whether the vendor is GST registered (not just ABN registered). Your client will not be entitled to an input tax credit if the vendor is not GST registered - Check the validity of any tax invoice provided at settlement.

For more information on GST issues see LPLC’s

• GST section on the website

• GST Checklist

• GST frequently asked questions

Why section 32 statements are defective

• Practitioners don’t ensure current and accurate information is used when preparing the section 32 statement. This often occurs when the vendor is in a hurry or there are unreasonable time frames. The practitioner may take shortcuts such as recycling old certificates or using an old copy of the certificate of title resulting in serious consequences for the vendor client

• Description of any easement, covenant or other similar restriction, like a 173 agreement registered on title, are not included

• Required current certificates like owners corporation certificates, water authority information certificate, building approval certificates, Heritage Victoria certificates and current plans of subdivision are not included

• Practitioners don’t accurately identify and indicate in the section 32 statement whether services are ‘connected’. Checking whether the vendor has a septic tank would have avoided some claims

• Practitioners don’t include information statements from the relevant water authority that provide current information about any unregistered easements affecting the land

• Practitioners don’t confirm that real estate agents have complied with requests made by the practitioner to amend, update or attach relevant certificates to the section 32 statement

• The location of property is not checked to see whether any potential growth area infrastructure contribution is payable for any growth area land brought into the Urban Growth Boundary 2005/06 or 2010 which is zoned for urban development.

CLAIMS EXAMPLES

Recycled certificates

The practitioner was instructed to prepare a section 32 statement within a day and did so using information from the file created several years earlier when acting for the client in the original purchase of the property.

The section 32 statement stated the property was zoned Residential C but failed to indicate there had been changes in the meantime resulting in the property being subject to a significant landscape overlay.

The purchaser’s practitioner did further searches and found this out. The purchaser rescinded the contract.

‘Short form’ section 32 statement

The vendor’s practitioner prepared the section 32 statement but a water information statement was not attached. After the contract was signed, the purchaser’s practitioner obtained a statement from the relevant water authority with an attached plan showing the course of a declared main drain running underneath the kitchen of the house. The purchaser’s bank refused to advance the finance to complete the purchase after being informed of the easement. The purchaser rescinded and demanded return of the deposit. The vendor resisted, but after costly court action the purchaser was successful.

Real estate agent held to account

On the instructions of the vendor who thought ‘connected’ sewerage included connection to a septic tank, the practitioner prepared the section 32 statement. Luckily, before the parties signed the contract, the practitioner picked up the error and instructed the estate agent to amend the statement to indicate the sewerage was ‘not connected’. Correctly, he kept a file note of these instructions. The section 32 statement was signed but the agent had not amended all copies of the statement; the vendor’s copy had been changed while the purchaser’s had not. The purchaser discovered the lack of sewerage and rescinded the contract. The vendor took action against the real estate agent and the practitioner. The practitioner had protected his position by keeping good file notes. Without these, the practitioner would have shared the liability with the agent.

Our recommendations

- When asked to prepare a section 32 statement on short notice:

- make it clear to your client and the selling agent that it takes at least a week to obtain all necessary certificates required to prepare a section 32 statement and a statement prepared in a hurry may be invalid

- point out to your client an invalid section 32 statement risks avoidance of the contract by the purchaser which may then involve double agent’s fees, delay and possibly a lower sale price

- let your client know an invalid section 32 statement also carries the risk of an action for damages for misrepresentation

- if despite this advice, your client insists the statement be prepared in a hurry, confirm the advice in writing to both your client and the selling agent.

[A pro forma letter can be found at Appendix One.] - Confirm whether an owners corporation exists and if so advise your client about the need to include owners corporation information in the section 32 statement even if the owners corporation is said to be ‘inactive’

[See Appendix Four for more details on this issue.] - Do not rely on the duplicate certificate of title. Always conduct an up to date title search

- Read the titles to ensure they are not a ‘half part or share’ of land. Assess whether the titles you have cover all of the land being sold

- Attach a copy of the Register Search Statement and the diagram location document. See LPLC’s article Determining the right diagram location document and section 32

- Consider having your vendor client complete the LPLC Sale of land questions for the vendor available for downloading from the LPLC website

- Apply for a fresh set of certificates and read each certificate carefully

- Make it your practice to obtain an information statement from the relevant water authority, which is necessary to establish whether there are any unregistered easements such as water, sewerage or drainage affecting the property or notices issued affecting the property. See LPLC article Make it a rule to include water information certificates

- Consider the possibility of unregistered easements. Question your client about the existence of agreements with neighbours or a neighbour’s use of an access track or water pipes across your client’s land relevant municipality relating to building approvals

- Include a plan of subdivision if appropriate

- Attach a planning certificate from the responsible authority

- Obtain a statement from the relevant municipality relating to building approvals

- Provide a condition report and certificate of insurance if the client is an owner builder (warranties go in the contract). See Appendix Two

- Make proper enquiries to ensure the section 32 statement accurately states which services are not connected. See section 32H. Avoid using the term 'available'

- When instructing estate agents to amend, update or attach relevant certificates to the section 32 statement, keep a file note of any verbal instructions and confirm those instructions in writing

- Carefully check a revised section 32 statement to ensure no documents have been left out

- Obtain instructions to make further investigations if necessary or if instructed not to do so confirm this in writing

For more information on Section 32 statements see the LPLC article Section 32 statements: the basics and the recorded webinar Building a better section 32 statement.

Many drafting errors occur in contracts of sale, rescission notices, transfers of land for subdivisions or where a contract has been renegotiated and subsequently changed.

Typographical errors in the transfer of land are by far the most prevalent mistakes. Very often an earlier draft of a restrictive covenant is transcribed on to the transfer and while they may look very similar, they specify

different lots for different restrictions or miss an important accepted use. Other mistakes have included omitting one of the titles to be transferred or referring to a dimension in a covenant as ‘meters’ instead of ‘square meters’. While it may seem like a formality, transfers of land need to be very carefully proofread to ensure they are accurate and the correct covenants have been used.

Mistakes frequently occur when precedents are not used properly. Common errors include failing to take out irrelevant clauses, for instance an abatement of rent clause that had not been agreed for a licence.

Clauses practitioners should check carefully are those dealing with remuneration for the vendor by way of rights to purchase, or receive in lieu of payment, a unit in the proposed development. These types of clauses have either been inexplicably deleted from subsequent drafts of contracts or not drafted well enough to protect the vendor in the event the development does not go to plan.

CLAIMS EXAMPLES

Error in contract of sale

The practitioner acted for a vendor who was selling part of his land. The vendor owned multiple adjoining lots in the same subdivision. All of the lots were recorded on one certificate of title. The practitioner was

instructed to sell only one of the lots in the certificate of title. The practitioner incorrectly described the land being sold as ‘all of the land in the certificate of title’. The error was only discovered after the purchaser became registered as the owner of all of the lots. To remedy the error, it was necessary for the purchaser to transfer land back to the vendor and this was done at the cost of the vendor’s practitioner.

Wrong precedent used

A practitioner was instructed to prepare an off-the-plan contract of sale but mistakenly included the

wrong sunset date in the contract. The instructions were that a period of 36 months was required to register

the plan of subdivision but a 12-month sunset date was inserted in the contract. A precedent contract

which had a 12-month sunset date was used and not amended. One purchaser rescinded based on the

12-month sunset date as the vendor was unable to register the plan of subdivision within the 12-month

period.

One crown allotment not included in the transfer of land

The practitioner acted for a purchaser of farmland involving seven crown allotments. When the transfer of land was prepared one of the crown allotments was missed.

The vendor and purchaser were notified of the error by the Land Registry a number of years after settlement. The purchaser’s practitioner spent a considerable amount of time resolving the matter and also paid compensation to the vendor for the time spent to rectify the error.

Our recommendations

- Always proofread contracts, rescission notices, transfers of land and double check the wording of any restrictive covenant

- When contracts are renegotiated, amended or reproduced always proofread them to ensure no clause has ‘dropped out’

- When using precedents, carefully check only relevant clauses have been left in

- Where the vendor is to receive other benefits under the contract besides payment at settlement, consider whether the relevant clauses adequately cover all contingencies

- When acting for multiple purchasers, specific instructions should be obtained relating to the manner of holding. Practitioners should not assume spouses and/or domestic partners wish to be recorded as joint proprietors

- Send the draft documents to the client for approval with explanatory notes of their purpose and meaning.

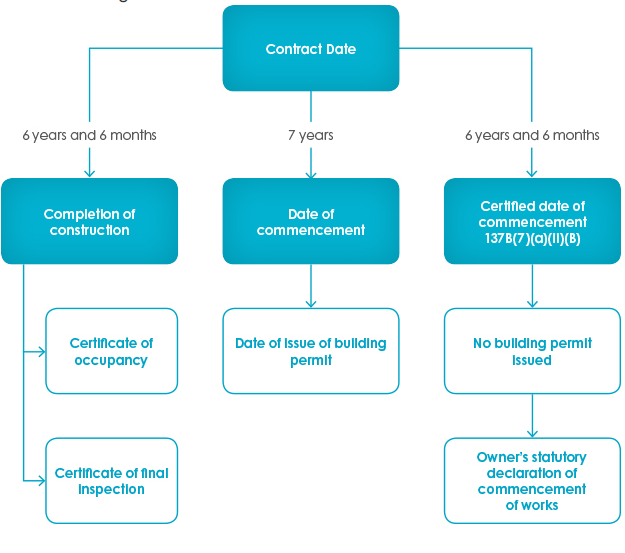

The complex provisions of the ‘owner builder’ sections of the Building Act 1993 (Vic), particularly as they relate to domestic owner builders, continue to catch practitioners out. Failure to ensure compliance with sections 137B and 137C result in the contract being voidable at the option of the purchaser at any time before settlement. The domestic owner builder requirements are summarised in Appendix Two.

When acting for a vendor, there are several common scenarios.

- The practitioner focuses on the pre-contract disclosure obligations such as building approvals within seven years, certificate of insurance and condition report, completely overlooking the need for the section 137C warranties in the contract.

- The practitioner assumes that because the domestic owner builder work is less than $16,000 in value, the requirements do not apply. The insurance requirements do not apply in these circumstances but the condition report and warranties are still necessary.

- When preparing a section 32 statement the practitioner forgets to check that the condition report is less than six months old or fails to warn the vendor or agent that the section 32 statement should not be used once the condition report is more than six months old.

- The practitioner doesn’t assemble sufficient information to make an assessment of whether the vendor is an owner builder. This is often coupled with a failure to warn the client of the consequences of non-compliance, including the purchaser being able to avoid the contract and the critical timing issues including that the requirements must be met pre-contract.

We have also seen claims against purchasers’ practitioners for failing to advise that the purchaser could avoid the contract because the vendor had not complied with the owner builder requirements. This often occurs because appropriate enquiries were not made to determine whether the vendor was an owner builder.

CLAIM EXAMPLE

Domestic owner builder works overlooked

The practitioner received instructions to prepare auction contracts and a section 32 statement for the sale of a residence. The practitioner knew a garage had been constructed by a registered builder but did not consider the status of a further addition of an extra room carried out by the vendor as domestic owner builder for $45,000. The section 32 statement prepared by the practitioner included a property information certificate from the local council listing both building permits. However, the section 32 statement did not include a condition report or a certificate of insurance in respect of the further addition and the contract did not include the warranties. The purchaser avoided the contract and the vendor incurred significant losses because there was a significant drop in the market and a much lower price was obtained on the resale.

Comments on the claim

A condition report which is no more than six months old at the time of contract prepared by a prescribed building practitioner such as an architect, building surveyor or building inspector must be given to the buyer pre-contract. Although it is common practice to attach an owner builder inspection report to a section 32 statement there is no legal requirement to do so.

Our recommendations

- Take detailed instructions from a client intending to sell domestic property including answers to the following questions.

- Have any building permits been issued in the last seven years or has there been any other building work in that time?

- Who did the building work? Unless a registered builder’s name is on the building permit, sections 137B and 137C will apply.

- What was the value of the building work? Was it more than $16,000?

- When did the building work commence?

- Was any occupancy permit or certificate of final inspection issued?

- Where your client is an owner builder warn them in writing of the need to provide insurance, condition report and warranties, and the consequences of non-compliance

- If the requirements apply, ensure the condition report and certificate of insurance are provided with the section 32 statement and the section 137C warranties are set out in the contract. Insurance is only required where the value of the building work is more than $16,000.

- When the section 32 statement contains an owner builder condition report, confirm in writing when sending the statement to the client or the real estate agent that the section 32 statement should not be used if the condition report is more than six months old and the consequences if it is used

- When acting for a purchaser, check in whose name any building permits were issued.

The domestic owner builder requirements are summarised in Appendix Two.

Many of these claims relate to ‘off-the-plan’ sales, although claims still arise where there are existing subdivisions particularly relating to identifying the right title and accessory units.

Practitioners acting for vendors get sued for:

• Transferring the wrong lot on a plan of subdivision, often because the lot number and street unit number are mixed up

• The contract for the sale of a lot on an unregistered plan of subdivision not complying with section 9AA of the SLA by not providing that deposit monies are to be held in accordance with that section, giving the purchaser the right to rescind pursuant to section 9AE(1) of the SLA

• Not promptly attending to registration of the plan of subdivision, giving the purchaser the right to rescind pursuant to section 9AE(2) of the SLA

• Failing to advise on the need to obtain owners corporation insurance as required by section 11 of the SLA

• Failing to draw clearly worded special conditions setting out the responsibility of the vendor and purchaser for certain works, usually in a subdivision development. For example, where both the vendor and purchaser have agreed to do certain building works but it is not clear which party is responsible for which works.

Practitioners acting for purchasers get sued for:

• Failing to spot a section 9AA or 9AE(2) breach, thereby depriving the purchaser client of the opportunity to rescind

• Failing to ensure car parks or accessory units are transferred

• Failing to advise there are no accessory lot(s) such as a car space

• Failing to detect a material difference between the proposed plan of subdivision in the contract of sale and the plan finally registered, usually with the lot size having been reduced, or a change in the boundary or an easement being added.

CLAIMS EXAMPLES:

Basement car park disappeared

The purchaser client bought an apartment off-the-plan expecting a basement car park to be included as part of the purchase. The registered plan was different to the plan in the contract and did not provide for the basement car park. Despite having correctly obtained a copy of the final plan prior to settlement, the practitioner failed to notice this. Settlement occurred and the client did not get what they had anticipated.

While the vendor had failed to comply with its obligation under section 9AC(1) of the SLA to notify the purchaser of a change to the plan prior to registration, thereby depriving the purchaser of the statutory right to rescind under section 9AC(2), the practitioner should have picked up the change prior to settlement. If the practitioner had done so, the client could have taken action to rescind on the basis the change represented a breach of a fundamental term of the contract.

Deposit monies not correctly held

The practitioner acted for the purchaser in an off-the-plan contract. A non-standard contract was used and breached section 9AA of the SLA by not providing for payment of deposit monies into trust. This failure provided the purchaser with grounds to rescind the contract at any time up to the date of registration.

When the purchaser encountered problems with the vendor developer, the practitioner did not pick up this failure and advise the client of this way out of the contract. Instead, lengthy disputation occurred which continued after settlement relating to significant building defects. The purchaser turned on the practitioner for failing to advise that they could have rescinded and avoided all the extra costs and inconvenience.

Cases to note

Practitioners preparing off-the-plan sales contracts should be aware of a number of cases that directly affect off-the-plan sales.

In Clifford & Anor v Solid Investments Australia Pty Ltd [2009] VSC 223 it was said that contract ‘sunset’clauses must specify a time for registration of the plan of subdivision in explicit terms and cannot be subsequently extended by the vendor.

In Everest Project Development Pty Ltd v Mendoza & Ors [2008] VSC 366 it was found the wording of the contract of sale did not comply with sections 9AA to 9AH relating to how the deposit bond could be called on.

The fixing of the registration date was considered in Harofam Pty Ltd v Allen & Ors [2013] VSCA 105 and Harofam Pty Ltd v Scherman [2013] VSCA 104. A special condition in the contracts of sale provided for a 24-month period for registration of the plan of subdivision (sunset clause) and this date could be extended once by six months. In reliance on the reasoning in Clifford, it was determined that this sort of clause breached section 9AE and the purchasers were entitled to rescind.

Sunset date legislation changes

The SLA was amended in 2019 to prevent a vendor rescinding residential off the plan contracts based on a sunset clause without:

- at least 28 days’ written notice to a purchaser before the proposed rescission

- a purchaser’s consent.

Section 10F of the SLA sets out the wording required for sunset clauses. For more information see LPLC’s Residential ‘off the plan’ sunset clauses legislation.

Our recommendations

- Carefully check plans of subdivision and contracts of sale to ensure the plan and the contract accurately describes what is being bought or sold

- Check any registered plan of subdivision carefully. Do not assume that because the subdivision plan number is the same as the plan attached to the contract, or that the vendor has not notified the purchaser of any amendments, that no amendments have been made to the plan

- When acting for a vendor of a lot on an unregistered plan, ensure your precedent contract complies with the obligations imposed by the SLA and warn the vendor of the consequences of any breach including that the purchaser may rescind. Specifically:

Section 9AA: the contract must provide that deposit monies be paid into the trust account of a legal practitioner, conveyancer or licensed estate agent for the purchaser until the registration of the plan of subdivision

Section 9AB: details of any works affecting the natural surface level of the land must be disclosed in the contract or, if carried out after the date of contract but before registration of the plan, must be disclosed as soon as practicable after details become known to the vendor

Section 9AC: the vendor must notify the purchaser of any proposed amendments to the plan of subdivision prior to registration and, if the changes materially affect the lot, the purchaser may rescind within 14 days of being so notified

Section 9AE(1): any breaches of sections 9AA and 9AB may result in the purchaser rescinding before the plan is registered

Section 9AE(2): the purchaser may rescind if the plan is not registered within 18 months, or such other period specified in the contract, of the contract date

- Advise your client of the insurance requirement imposed by section 11 of the SLA if the lot is affected by an owners corporation. Unless the owners corporation has the required insurance, the purchaser may avoid the sale at any time before settlement

- When acting for a purchaser, check compliance by the vendor with the SLA’s obligations and, if there is non-compliance, advise your purchaser client of the right to rescind

- Advise your purchaser clients of the expiry date for any planning permit including for the subdivision of land and the consequences for failing to meet the deadline. Unless there is a contrary provision, a planning permit for the subdivision of land expires five years after certification of the plan of subdivision. See section 68(1)(b) of the Planning and Environment Act 1987. Once the period has expired, the plan of subdivision will need to be recertified by the council and that can be costly. In some instances it may also be necessary to apply for a new planning permit to subdivide the land.

This category of claims relates to mistakes in advice given by practitioners acting for purchasers.

There are three common scenarios.

- The practitioner gives no or inadequate pre-contractual advice on a pertinent issue. The client later alleges that if proper advice been given, they would not have signed the contract

- The practitioner fails to make post-contract enquiries and searches. The client later alleges that if the enquiries had been made, information would have been disclosed giving the client the right to rescind

- The practitioner’s post-contract searches and enquiries reveal some critical information the vendor did not provide in the section 32 statement, which is not passed on to the client. The client later says they would have attempted to avoid the contract had they known of the information.

Specific errors made by practitioners include failing to:

- Advise on zoning or planning scheme matters or the existence of a restrictive covenant resulting in the client being unable to use the property as intended

- Detect the existence of drainage/sewerage easements resulting in the purchaser client being unable to build or extend where intended on the property

- Detect discrepancies in the section 32 statement, particularly as to whether services are connected to the property

- Advise on breaches of a lease and/or unusual lease provisions involving tenanted commercial premises, such as:

- worthless rental guarantees

- the existence or non-existence of options to renew

- whether a five-year term has been created by virtue of section 21 of the Retail Leases Act 2003 (Vic) or

- the early termination rights of the tenant - Advise the client to check and/or measure the boundaries of the property

- Adequately handle all issues relating to water allocation and shares

- Obtain a VicRoads certificate disclosing the land was subject to a proposal to acquire the land

- Advise on building notices

- Advise on the conditions in any crown grant

- Advise on the expiry of a planning permit

- Advise on nomination rights.

CLAIMS EXAMPLE:

No advice on building approvals

The client entered into a contract to purchase the land and a Bed and Breakfast business. The section 32 statement showed there were no building approvals in the last seven years. The client’s practitioner did not apply for a building approval certificate, warn the client of the risks of not doing so or to make enquiries with council. When the client went to sell the land several years later it was discovered a building permit had been issued to the original vendor but no final inspection had ever been undertaken and the council had required works to be done to rectify the illegal structures. A claim was made against the practitioner for the cost of rectification works and the difference in the sale price once the new purchasers discovered the problem.

Client not informed about easement

The practitioner was instructed to act for a purchaser post signing of the contract. The section 32 statement was 18 months old and since it had been prepared, a plan of subdivision had been approved with a three-meter sewerage easement at the rear of the property. The practitioner did the necessary searches but failed to draw the client’s attention to the easement prior to settlement. As a result, the client lost the chance to either rescind the contract or perhaps negotiate a lesser price and had to relocate the sewerage line.

‘Available’ not connected

A section 32 statement indicated sewerage was ‘available’ and the purchaser client assumed ‘available’ meant connected. The client’s practitioner applied for an information statement from the local water authority. On the back page of the statement it was noted the property was likely to be part of a sewerage development in the future and the landowner would be required to contribute to the cost. This was not detected by the practitioner who only read the front page. After settlement, the client discovered the sewerage was not connected, blamed the practitioner and sought to claim the difference in value between the sewered and unsewered land.

Our recommendations

When providing pre-contractual advice

- Ask the client what they intend to do with the property and use this information to inform your review of the section 32 statement and the contract

- Warn the client to check with the local council about any use requirements. It may be that the intended use is prohibited and/or the current use is in breach of the planning scheme

- Carefully check the contract, section 32 statement and associated certificates. If anything unusual is detected, warn the purchaser client and confirm your advice in writing

- Be on the look-out for zoning issues, planning overlays, restrictive covenants and unusual lease provisions where tenanted commercial premises are involved

- Obtain instructions to make further investigations if necessary or if instructed not to do so, confirm this in writing with the client

- Consider the need to obtain details of any lease(s) affecting the land.

When instructed to act post-contract

- Ask the client what they intend to do with the property and use this information to inform your review of searches, the section 32 statement and the contract

- Apply for a full set of certificates, particularly where the section 32 statement contains certificates that are outdated (three months old as a ‘rule of thumb’) or incomplete, for example where it does not include a water information statement disclosing any unregistered easements. Some property reports are freely available through the Victorian Property and Parcel Information Search

- Make sure you carefully compare the results of your searches with the information in the section 32 statement. Advise your client of any discrepancies or differences and the client’s rights to avoid the contract, if any

- Always advise your client to check and/or measure the property and point out to them the shape of the property on the title. Where the client is buying an apartment, it may assist the client if you highlight the relevant lot(s) on a copy of the plan of subdivision

- In the event that a section 32 statement indicates services are ‘available’, advise your client that ‘available’ may not mean connected and further enquiries should be made to determine which services are connected

Always review any related documents contained in the section 32 statement such as a covenant and provide advice regarding all relevant terms.

Conditional clauses, like ‘subject to finance’ continue to catch purchasers and their practitioners out.

For subject to finance clauses there are some common errors.

- The practitioner and/or the client fail to realise the pre-approval letter from the financial institution is not a final approval and is conditional on a valuation. When the valuation is obtained it is too low for the purchaser’s needs but by then the contract has become unconditional

- The practitioner and/or the client do not realise the amount approved for finance is less than required

- The client is not given sufficient warning by their practitioner of the requirement to notify the vendor in writing by a specified time if finance cannot be obtained and the consequences of not doing so

- Delays occur in seeking an extension of time for finance approval or notifying that no finance was obtained, usually caused by oversight or administrative errors.

CLAIMS EXAMPLES

Client not warned

A practitioner wrote to their purchaser client soon after receiving instructions to act in the purchase and informed them of the date by which finance needed to be approved. The practitioner also asked the client to notify the practitioner if finance had been approved by the required date. He did not warn the client of the consequences of not providing the information in time. The client appeared to be relatively sophisticated and the practitioner assumed the client knew the consequences.

When the approval letter was received, it was for less than the client required and subject to valuation. The client did not tell the practitioner until sometime after the approval date. The client alleged he thought if he could not get finance, the contract was automatically avoided. He says he did not realise the vendor had to be notified by a certain date in order to avoid the contract.

Client doing some of the negotiating

The purchaser’s bank was not prepared to lend the purchaser the amount they needed because the valuation was less than the purchaser had agreed to pay. While the purchaser’s practitioner was negotiating with the vendor’s practitioner about an extension, the purchaser spoke directly with the vendor and arranged an extension of time to obtain another valuation. The purchaser’s practitioner was told of the oral extension by his client but did not confirm it in writing.

When the purchaser received the second valuation, he decided to avoid the contract but the vendor said the extension was only to allow the purchaser to make an application for finance from a specific bank and the contract had now become unconditional.

The purchaser’s practitioner was blamed for not having told the client to avoid the contract when the first approval date was looming and for not confirming the extension date in writing. It could be said the client was very bossy, wanting to do his own negotiations and the practitioner let himself be pushed around.

Our recommendations

When a contract has a ‘subject to finance’ clause a number of things need to occur.

- Write to your purchaser client immediately on receipt of the contract setting out clearly the date by which finance must be obtained. Spell out the consequences if the vendor is not notified in time that finance has not been obtained

- Confirm with the client any approval they receive is in writing, is final and not conditional, and is for an amount sufficient for their needs. Where time permits, ask the client to give you a copy of the letter of approval for finance and ensure you check these points

- If the approval is conditional, seek instructions to request an extension of time until the conditions have been met

- Do not leave requests for extensions of time for finance approval unanswered. Chase up the answer before the time expires

- Confirm any oral agreement to extend time in writing

- When time is about to expire, pay careful attention to requests for extensions or notification that the contract is at an end. Take steps to ensure letters dictated are actually typed and sent or faxes or emails are sent to the correct person/places.

For more information see LPLC’s:

• On the subject of finance – Part 1

• On the subject of finance – Part 2

• Not so perfect putt

• What subject to finance really means

This category usually involves a problem with lost titles or unstamped and unregistered transfers of land. This latter category is less likely to happen today with electronic conveyancing, however there are still instances of paper transactions where practitioners need to be careful.

These claims arise in the following types of scenarios.

- Titles are discovered missing just before settlement because:

- they were never transferred when the client bought the property, sometimes because no one realised there were multiple titles for the property or the title was only for a part share in the property

- the transmission application after the death of one owner was never completed

- the firm who held the title no longer exists and it takes time to track down what happened to their deeds room documents - There are special conditions on the contract which required other things to be done before settlement could occur such as obtaining an easement over adjoining property or the purchase of other property. The practitioner loses sight of those conditions and doesn’t pursue them, resulting in delay

- Administration errors where documents, often transfers with title deeds, are sent back to the practitioner’s office for amendments and mistakenly put on the file. The file is then closed without anyone checking what is sitting on the file

- The documents are lost or delayed in transit or at a third party’s office, such as the local council, bank or surveyor and the practitioner doesn’t do enough to chase up the matter.

CLAIMS EXAMPLES

Half share titles

The sale contract indicated the property consisted of five titles but prior to settlement the purchaser’s practitioners discovered that two titles were missing. Two of the existing titles were only ‘one equal undivided half part or share of the land’ and so the other ‘half part or share’ titles needed to be found. The previous vendor had failed to convey those titles and refused to do so when the current vendor requested them.

Three months after the problem was discovered, proceedings were issued to compel the previous vendor to transfer the titles. Those proceedings took 12 months. Just as they were resolved in the current vendor’s favour, his practitioner discovered a third title was missing. This time it was the title to a narrow strip of land that had been previously conveyed by the council to the previous vendor. Again the previous vendor would not hand over the title and further proceedings had to be issued. The total delay as a result of the missing titles was three years and eight months. The delay was argued to have cost both the vendor and purchaser significant damages.

Missing titles

The firm acting in the conveyance only asked for the title from the client’s previous firm that was supposedly holding it just before settlement. The previous firm was unable to locate the title or what might have happened to it. Settlement was delayed by 45 days while searches were undertaken and then a new title application was made. The client claimed the holding costs and lost interest on the settlement proceeds during that time. Both firms shared some responsibility for the loss.

Converting paper titles to electronic titles

One emerging issue to be aware of in relation to electronic conveyancing is the need to destroy or make a paper title invalid in certain circumstances. If you don’t hold an existing paper title you must still take possession of it in order to truthfully complete the certification required in clause 6 of schedule 3 of the ARNECC Model Participation Rules that you have destroyed or made the paper title invalid. You should confirm with your client whether they want the paper title destroyed or made invalid.

For more information about this issue see LPLC's:

• Land dealing certifications need to be taken seriously

• Destroy titles or make them invalid?

Our recommendations

- Act quickly at the start when acting for the vendor to find and secure possession of the paper or electronic title

- Carefully review the title(s) to ensure there is nothing missing, in particular check the nature of the interest and don’t just assume it is full estate in fee simple

- Inform the client at the first opportunity of your estimate of the amount of stamp duty and lodging fees payable. You may need to consider any stamp duty concessions, exemptions and/or the right to apply for the first homeowner’s grant

- For any paper title transactions:

- keep track of the date by which a document must be stamped, especially a transfer of land must be stamped no later than 30 days after settlement. Diarise for follow-up action regularly, such as weekly

- advise the client of the date by which any funds must be provided to enable the documents to be stamped and registered within time and the consequences of missing the deadline. It is safest to seek the funds well before settlement

- notify the client in writing that you accept no responsibility for reminding the client of the due date to provide funds to your office for stamping and registration.

It should go without saying that settlement funds should not be disbursed without first obtaining instructions, preferably in writing, but we continue to see mistakes in this area.

These claims arise in a variety of ways including the following scenarios.

The silent vendor: The law firm acts for several parties who own property either as joint proprietors or as tenants in common. Instructions are given by just one of the vendor clients as to how the proceeds of sale are to be disbursed at settlement. When that client absconds with the money the other, ‘silent’ vendor client argues that the law firm had no authority to disburse the money as they did.

Owners in dispute: The law firm acts for one of several owners of property who are in dispute. Often a matrimonial or de facto separation is involved. The parties agree the property will be sold and the proceeds of sale are to be held by the law firm pending resolution of the dispute. At some point the client gives instructions for the proceeds to be paid in a certain way and the operator at the law firm either does not know or does not remember and takes no steps to check the basis on which the money was being held. They therefore pay the money out as directed and in breach of the trust on which the money was being held. While the law firm does not act for the other disputing vendor, it nevertheless owes them a duty to act in accordance with the agreed trust and cannot just act on its own client’s instructions if this involves a breach of trust.

Our recommendations

- Revisit the basis on which money is held in the trust account before money is paid out of the trust account

- If it was agreed that the money would be placed in a joint interest-bearing account in the names of both parties or paid out to discharge a particular debt:

- then that is what must happen regardless of your client’s contrary instructions

- where the parties cannot agree on how the money is to be paid out and the terms of the trust do not squarely deal with the situation, do not pay it to your client or the party who shouts the loudest. Rule 12 of the Supreme Court (General Civil Procedure) Rules 20015 (Vic) sets out a procedure for a stakeholder’s interpleader. Practitioners are urged to pursue this procedure where it is available - Keep a file note of the instructions to disburse money and when given verbally, confirm the instructions in writing

- Obtain written authority from all vendors before disbursing the balance of settlement monies to one of several vendors

- Proactive supervision of employed practitioners and clerks, and properly training them so that they understand why it is important to obtain instructions relating to the disbursement of settlement funds.

These claims continue to arise mainly where the practitioner acts for an existing client who wishes to transfer property, or in some cases gift the proceeds of sale of a property to a family member to buy another property, usually a child. The practitioner often then also acts for the child.

The arrangement is usually done on the basis that the former-owner-client is entitled to live in the property for the rest of their lives. Subsequently the parties either have a falling out and the former owner leaves, or the new owner mortgages the property and goes into default. In either case the former owner wants to undo the arrangement.

Allegations are made later that the practitioner preferred the interests of the new owner and failed to advise the former owner of all the risks.

The failure to advise that CGT may be payable on the transfer of the property can also be an issue.

Always consider CGT, duty, land tax, GST, Growth Area Infrastructure Contribution, first homeowner grants and any affect to pension entitlements that may apply to any transfer between family members or related entities. If any of these are applicable, recommend to the client they consult with their taxation/accounting advisers before any transfer proceeds.

CLAIM EXAMPLE

Lack of ‘useable trail’

An elderly client came with her granddaughter to see the practitioner and instructed that she wished to have the property transferred to the granddaughter so the granddaughter could obtain a loan for extensions to the home. In return, the client could continue to live there.

The practitioner advised against the arrangement but failed to advise that an alternative would be for the client to retain the property and obtain a loan with the granddaughter acting as guarantor. The transfer proceeded and there was the inevitable falling out several years later.

The client alleged the practitioner did not protect her interests and failed to give her any warnings. The practitioner maintained he did warn against the arrangement but could not prove it as he had not kept any file notes or sent the advice in writing.

Our recommendations

• Never act for both parties in intrafamily transfers. Remember a deterrent excess applies where a practitioner acts for more than one party in a matter. See clause 5 of the LPLC insurance policy

• When the other party is unrepresented, tell them you are not acting for them and recommend the party obtains separate representation and advice. Confirm this in writing

• Warn the transferor client in writing of the dangers in these types of arrangements, particularly that the transferee will have the right to encumber the property

• Find out what the transferor client is trying to achieve by the transaction and consider if there are other ways of achieving the desired result. Advise your client of those options. For example, a transfer and mortgage back to the transferor may be appropriate in some circumstances

• Warn the transferor to seek advice from an accountant about possible CGT liability if the property is not the longstanding residence of the transferor

• Also see further information on Senior Rights Victoria’s website and in particular their booklet ‘Care for your Assets: Money, Aging and Family’ at www.seniorsrights.org.au.

For more information see LPLC's:

Dealing with a default situation, whether your client is in default or seeking to enforce the contract, requires a thorough understanding of the issues, the contract in question as well as good communication with your client and accuracy and attention to detail.

Claims relating to rescission of a contract of sale usually arise because practitioners:

• Fail to strictly comply with the notice requirements in the relevant contract of sale because the rescission notice is defective as it:

• does not accurately specify default

• does not accurately specify when the default must be remedied as required in the contract

• is not served as required in the contract

• Fail to advise their client on all their options relating to a default and/or the right to rescind

• Delay in serving rescission notices

• Accept extensions of time without instructions

• Fail to advise clients about the consequences of default or not complying with the default or rescission notice.

A regular enquiry LPLC receives is whether a vendor can rely on a rescission notice when the vendor is not ready to settle. In Barrak Corporation Pty Ltd v Jaswil Properties Pty Ltd [2016] NSWCA 32 the court said no.

In this case the vendor issued a rescission notice. The matter proceeded to settlement before expiry of the notice but it was discovered at settlement that the vendor was not ready to settle as the transfer of land had been incorrectly executed by the vendor. The execution clause was mistakenly prepared by the purchaser’s representative for an individual person to sign rather than the corporate vendor execution.

Settlement did not proceed.

The vendor sought to rely on the original rescission notice when the date to comply expired. The court stated that the vendor could not exercise its rights to rescind as the vendor was not ready, willing and able to complete.

CLAIMS EXAMPLES

Serving a second rescission notice without instructions

A vendor’s practitioner served a rescission notice when the purchaser failed to pay the balance of the deposit by the due date but it referred to the wrong amount outstanding because the vendor’s practitioner failed to take into account a part payment of the deposit of $500, which was paid to the selling agent on signing of the contract of sale.

When this was pointed out by the purchaser the practitioner sought advice from counsel who believed it was arguable as to whether the notice was defective.

To protect the vendor’s position, the practitioner issued a second notice of rescission. This notice was issued without seeking instructions from the vendor client. The purchaser was able to settle within the 14 days of

service of the second rescission notice.

The vendor brought a claim against the practitioner on the basis the second notice should not have been served without first seeking instructions from the vendor. Had those instructions been sought the vendor would have instructed the practitioner to rely on the first rescission notice. The vendor believed the property could have been resold for an amount greater than the original contract.

Failure to advise purchaser of consequences of rescission

A practitioner acted for a purchaser of a rural property who failed to pay the balance of deposit by the due date and as a consequence the vendor issued a rescission notice.